She Was Called Rose

The '10 Million Names' project, an initiative focused on assisting descendants of enslaved Africans recover their family name, reminded me of the value of being able to trace parts of my lineage.

I know a huge piece of my story, and I want this for every Black American.

When I first heard about the 10 Million Names project, I wondered if my ancestry could trace back farther than the paperwork my dad’s family had been afforded as Louisiana Creoles.

According to its website, 10 Million Names is a collaborative project dedicated to recovering the names of the estimated 10 million men, women, and children of African descent who were enslaved in pre- and post-colonial America (specifically, the territory that would become the United States) between the 1500s and 1865. Its mission is to amplify the voices of people telling their family stories for centuries, connect researchers and data partners with people seeking answers to family history questions, and expand access to data, resources, and information about enslaved African Americans.

In my dad’s family, her “name” was Rose.

My oldest known enslaved ancestor ironically bore the given name that I’ve been wearing as a married surname. Our connection begins there.

After learning her name, I sought to find her. Like a closed adoption to the descent, seeking her out relied heavily on unsealed records from other deceased ancestors.

I can only imagine the truth of her story, so widely told throughout Iberville Parish, Louisiana. Rose was an enslaved Nigerian first held captive in Jamaica before boarding La Golondrina in 1779 for the voyage to Louisiana, where she became the property of Pierre Belly, a French-born British man who had inherited 3,756 acres of land, the area now known as White Castle, LA.

Intrigued by Rose, whom he could not marry, Pierre began quite the public relationship with her, a union that bore six mullato children. During his service as a judge, the couple used the courts to legalize aspects of their unofficial marriage, including providing Rose and their daughters' freedom and inheritance of his property. (Rose died at about age 70 in 1825.)

Pierre died in 1814 with over 8,500 acres of land, including five plantations. At his death, he was the wealthiest planter and largest land and enslaver in Iberville Parish. His grandson, Antoine Debuclet, Jr., a product of his union with Rose, would carry on the family tradition when by 1860, he was considered the wealthiest Black slaveholder in Louisiana. Broken by the Civil War, Antoine later served as the first Black Louisiana State Treasurer. He is enshrined in the state’s Black History Hall of Fame, a fortune he stacked on the backs of a family built on American slavery.

I can only brag that I am not a member of his direct lineage.

Pierre and Rose’s daughter, Rosalie, had 11 children, including Evelina. Evelina married Manuel Macias, and they were the parents of Marie Regina, who married John Amar. Regina and John were the parents of Lopez Amar, who married Pauline Barra, with lineage in Cuba and Haiti. Lopez and Pauline were my paternal grandmother Evelyn’s parents. I’ve seen their photos – they accurately depict everywhere and nowhere. This family’s history begins in Louisiana because it can’t definitively trace back anywhere else.

My father’s DNA, among the mixed bag of ancestry, showed just 6% Nigerian ancestry. Throwing bleach on colors leaves indelible stains – emptiness. To know Rose’s “name” and be so far removed from her is only to imagine that the African features neatly placed on his light skin were the gifts of her ancestry. A little piece of who you are with remnants of whitewashed memories that you can’t confirm was good or bad. I can trace Pierre’s family back to the 1400s, but I struggle to consider them my ancestors when so much of my identity is lost to them.

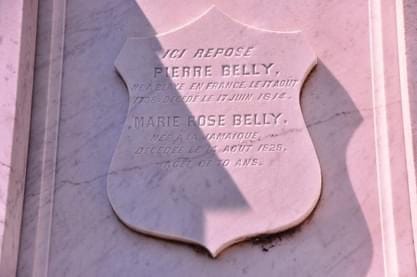

In the 1860s, Pierre and Rose’s grandson, Pierre Cyprien Ricard, had his grandparents’ remains moved from one of Pierre’s plantations to St. Raphael Cemetery in Bayou Goula, LA. It was August 2011, the first time I saw the grave of my only traceable African ancestor. In 2015, I worked in a neighboring parish and often found myself called to visit. I responded to the call that felt like my name echoing in the wind of a place where my ancestors became the flames of the Civil War. The ashes left behind became the dust scattered in the rundown cemetery that runs along a desolate highway leading to the place in my grandmother’s stories. The home that I’m just two generations removed from and yet can only imagine the landscape.

I hope we can all uncover what’s been lost and restore the legacy of the decedents who call to us so that we can recognize their voices when they call our names.

Leslie D. Rose is a journalist, creative writer, and communications strategist. She often lends an advocacy lens to her cultural pieces, giving a charge to the audience while presenting a new view. She interviews your favorite celebrities, uncovers deep issues affecting Black folks, and has written extensively about the negative impact of using rap lyrics as evidence on trial. Leslie is a proud Xavier University of Louisiana graduate.